Scheduling in React 16.x

What is scheduler?

Let’s start with some theory.

JavaScript is a single-threaded language. This means we have one call stack which can perform one piece of code at the time. Among executing your code, the browser needs to perform a different kind of work. This includes:

- managing events (user clicks handlers,

setTimeoutcallbacks, etc.) - layout calculations (building DOM / CSSOM) and

- repaints (based on the layout calculations)

Let’s focus on the last one. Within one second, browsers usually repaint 60 times, which means there is a single repaint every 16.6 ms (more or less, depending on the environment).

When you run a piece of synchronous code for about one second, you will accidentally drop ~60 frames which introduce delays, hits UX, and makes your app unresponsive.

So, the primary objective of the scheduler is to balance between all the activities being performed within the browser, not starve any of them as well as keeps your app repaint-aware.

But, as developers, should we care? No doubt, we should be aware of the problem. Nowadays, we outsource quite a lot of responsibilities to third party entities while developing our apps.

Web frameworks do a lot for us, they manage routing and state, provide change-detection mechanisms, two-way-data-binding (Angular/Vue.js), update DOM directly, and many, many more. They act as a middleware between us and the browser, so it seems to be a great place for scheduling problem to be solved, right?

And web frameworks do so. There is no exception for React as well (at least, React 16.x).

Trying to implement a simple scheduler

I will explain how it is managed by React, but, to understand the underlying problem, let’s write some simple piece of code…

Let’s simulate a heavy browser app:

setInterval(() => {

document.body.appendChild(document.createTextNode('hi'))

}, 3)

It forces the browser to do a repaint (caused by DOM manipulations being made each 3 ms). Now, consider this code:

setInterval(() => {

document.body.appendChild(document.createTextNode('hi'))

}, 3)

render()

function render() {

for (let i = 0; i < 20; i++) {

performUnitOfWork()

}

}

function performUnitOfWork() {

sleep(5)

}

function sleep(milliseconds) {

// sleep for given {milliseconds} period (synchronous)

}

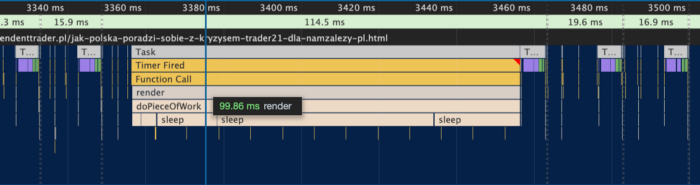

What is the impact of our browser rendering mechanism? Well, render is synchronous, so it freezes browser for 100ms (20 * 5ms = 100ms). No repaint can be made within the time. User input event callbacks neither. Let’s take a look into Chrome’s “Performance tool” output for a given code:

In the example, we drop frames for more than 100ms (see vertical dotted lines, they show you when the frame ends). As mentioned earlier — the browser does a repaint each ~16.6 ms (60 frames per second). In this case, repaints are delayed which freezes any animation performing at the time. User input handlers are delayed as well. This is not what we want, right?

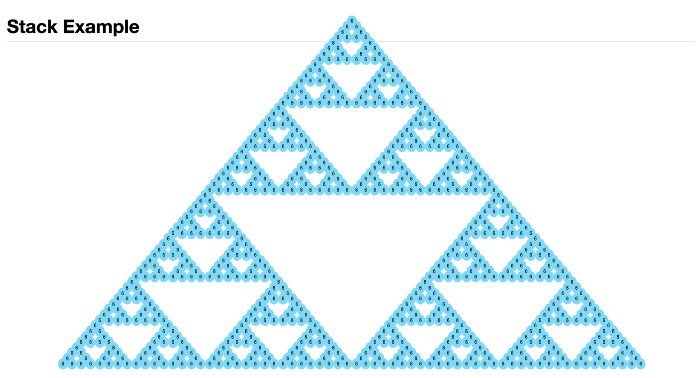

Now, let’s assume the provided render function is a React 15.x implementation of render mechanism. During the process, React tracks changes, calls our life-cycle methods, compares props, etc. It is a time-consuming process that might take a long time to compute, especially in heavy apps.

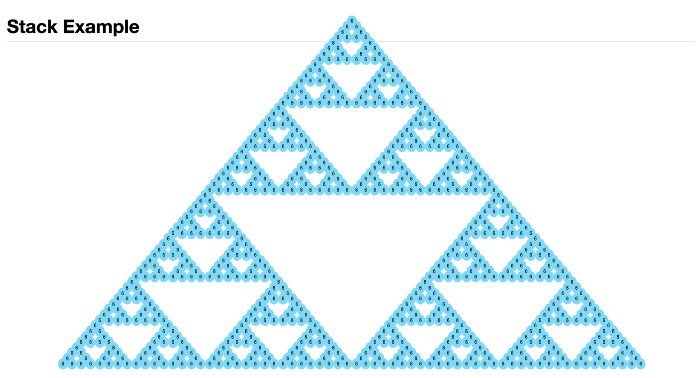

Does the React 15.x have a scheduler mechanism at all? Nope, it does not, so there is no difference between our synchronous render function and React 15.x render implementation. Here is an example React 15.x application , which do a lot of computation, without scheduler implementation:

Quiet laggy, right? Let’s go back to our example… How can we improve this synchronous-based rendering mechanism? How about adding setTimeout?

...

function render() {

performUnitOfWork()

setTimeout(render, 0)

}

...

What are the results?

Yep, way better, our frames are no longer delayed. Our performUnitOfWork function is being handled separately, on each frame. Repaints are being made regularly — with no frame delay.

So, is it the way the scheduling problem is being solved for React 16.x apps? Not really. Among entire internal engine rewrite (so-called React Fiber) React team has introduced a dedicated module - “React Scheduler” - to address scheduling issues. How it works? I will explain it soon, but firs t— we need to introduce… Channel Messaging API.

MessageChannel-based scheduling

What it does is a simple thing. It lets you communicate across different JavaScript contexts, i.e. between your code and iframe, or between your code a web worker’s context.

Consider the following example:

// index.html

<iframe src="iframe-page.html"></iframe>

<script>

var iframe = document.querySelector('iframe')

var channel = new MessageChannel()

iframe.addEventListener('load', () => {

channel.port1.onmessage = e => console.log(e.data)

iframe.contentWindow.postMessage('hi!', '*', [channel.port2])

})

</script>

// iframe-page.html

<script>

window.addEventListener('message', event => {

console.log(event.data)

event.ports[0].postMessage(

'Message back from the IFrame'

)

})

</script>

What you need to do is to set a listener on one port (port1), and transfer another (port2, which will be used by sender) into another context (i.e. to iframe) using postMessage API. Then you can communicate in both directions.

But do we need to communicate with iframe or WebWorker in our app? Not really, but the API (alongside communication capabilities) has another advantage. It lets you kindly schedule work that respects other browser activities, such as rendering, DOM calculation, etc.

How? By the so-called “messages loop” mechanism. Now, let me replace the previous implementation of synchronous render function with this:

setInterval(() => {

document.body.appendChild(document.createTextNode('hi'))

}, 3)

const channel = new MessageChannel()

render()

function render() {

channel.port1.onmessage = onMessageReceived

channel.port2.postMessage(null)

}

function onMessageReceived(event) {

performUnitOfWork()

channel.port2.postMessage(null)

}

function performUnitOfWork() {

sleep(5)

}

Our render function was updated to take advantage of MessageChannel API. We just created the “message loop”. Sending a message on port2 (inside render function) forces onmessage (which is onMessageReceived) to be called, which do some calculations (performUnitOfWork). Then once again it forces sending a message on port2, which eventually… yep… you see the pattern, right? That is how the message loop is created.

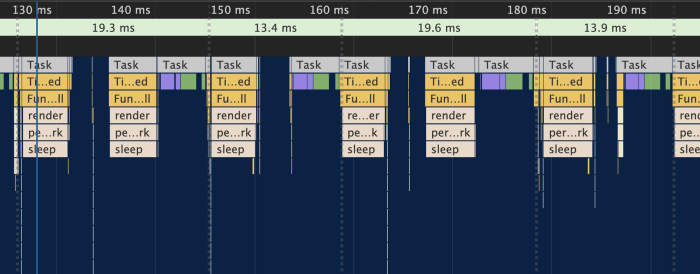

Now let’s look at our performance profile:

Repaints are being made each 14ms / 19ms. During the single frame, we can see performUnitOfWork is executed even 3 times which is better than setTimeout approach. What is more, in the setTimeout solution there were lots more empty spaces between “execution bars” where the browser does nothing. It’s not the case in the message loop.

Scheduling in React 16.x

And here comes the fun part. I just described to you how does the most recent implementation of React Scheduler works. It uses the MessageGlobal API to achieve their in-browser scheduling goals. This approach is even better comparing to the setTimeout implementation, as it is eventually able to perform even more work within the frame.

Now, this approach requires splitting a work into smaller chunks. Our example implementation of render function performs computation (performUnitOfWork) for about 5ms. And there is no difference for React implementation — it also splits work into smaller chunks to be executed within 5ms.

Why do we want to break our execution into smaller chunks? To let the main thread to execute pending events / do repaints / manage animation in the meantime, so there are no UX lags.

Consider this piece of React code:

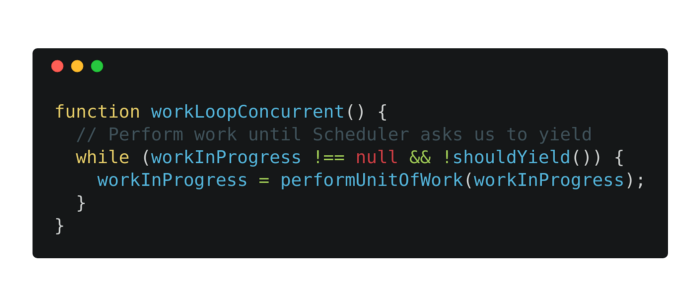

This is one of the most important fragment of React code. Main work loop. As mentioned earlier, the latest version of React (in the contrary to React 15.x) lets you split work into small chunks (workInProgress). Each of them is being handled (performUnitOfWork) one by one, as long as:

- we have some work to do (

workInProgress !== null) - and

shouldYield()returns false.

So many synchronous work is being made within the performUnitOfWork. This piece of code comes from React’s “reconciler” mechanism. If you would like to find out more how React works under the hood, I strongly recommend you to search for “React Fiber” phrase. For the sake of the article, let’s assume performUnitOfWork is a function that walks our component tree, do change-detection computations, including call lifecycle methods, side-effects marking. It is a heart of React render process.

React Fiber is designed in the way, that each finished work result is being saved on the heap, so we can interrupt a workLoopConcurrent loop any time, and return to this later on.

But how do we know when to interrupt this work?

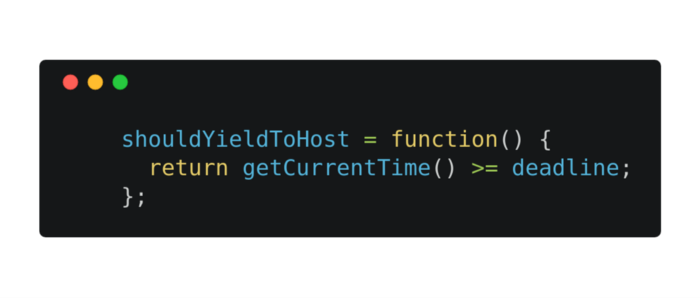

Here comes the shouldYield function which is a part of a “Scheduler” module. It has one responsibility — to decide whether to stop or continue working on tasks (performUnitOfWork). It returns true when we should stop computation and yield to the main thread, or false when we should proceed with our computation.

What is an implementation of shouldYield?

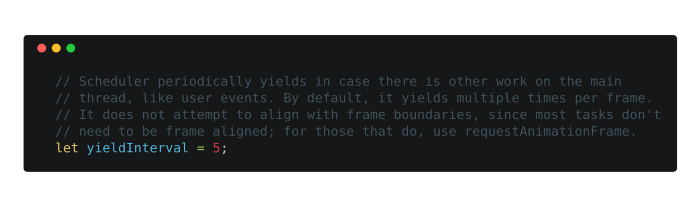

It checks whether we exceeded the deadline. What is the deadline? It is a currentTime + 5ms, so it appears, React scheduler breaks the execution each 5 ms, so the same, as presented in our example earlier in the article. There is a descriptive comment in the source code presenting the way it works:

Ok, where is a code presenting MessageChannel loop?

It’s a little bit more complicated, but at the very bottom of the code listing, we have a channel setup. You can briefly walk through the code comments to see the flow. Inside performWorkUntilDeadline there is port.postMessage(null); which keeps the message loop running.

We have also a piece of code, which prepares deadline (deadline = currentTime + yieldInterval;)

What is scheduledHostCallback? Long story short, it eventually triggers workLoopConcurrent presented earlier, which is the main work loop for the React render process. But the function is designed to return information, whether work is done or we should continue in the next message loop iteration (hasMoreWork).

Remember React 15.x app example which presents scheduling problem?

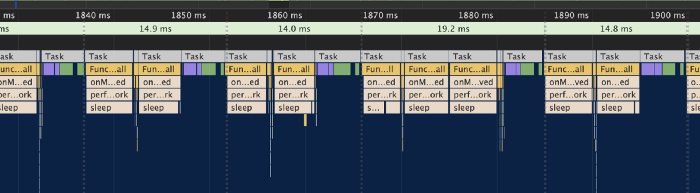

Here you can see the same app but powered with React 16.x and its new React Fiber approach. Way better, right?

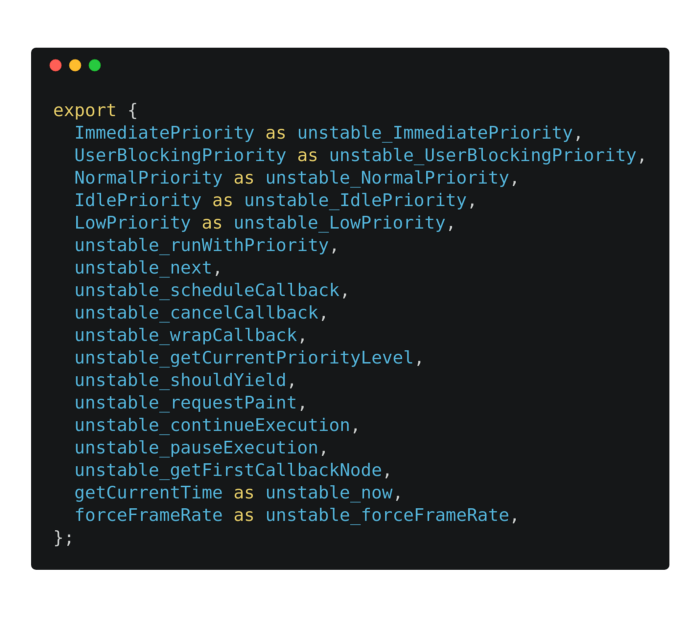

React’s Scheduler Module

shouldYield is not the only API exposed to the internal use for React devs.

Considering the naming convention of the exposed functions, we can conclude the module is still in development stage and API might change at the time.

Beware! This API is not intended to be used by the developers (like you and I). It is only for the team members/contributors internal usage. Of course, we use it, but indirectly.

You can see that the module exports function runWithPriority as well as some predefined constants (UserBlockingPriority, NormalPriority, LowPriority). It is not yet widely used in React, but the purpose of this is to let React schedule work with different priorities. We can expect more use cases to be supported with this API in further React releases.

What is the goal of such logic? To prioritize render of specific elements. In the Facebook app, it is more important to see news feed in the first place rather than header, footer or authenticated user section. In this case, we might render news feed related components with higher priority.

That’s the goal, hope to see some real use cases in upcoming React releases. It’s the future, but how about now? Where do we schedule a task using the Scheduler Module?

Well, hook’s effects are being scheduled using React Scheduler Module.

There is an enigmatic enqueuePendingPassiveHookEffectMount function which schedules scheduleCallback tasks with NormalPriority.

Let’s focus on the function name (enqueuePendingPassiveHookEffectMount) and find out what each name piece means:

enqueuePending…: Scheduler module under the hood builds a list of callbacks (and assigned to it priorities) that needs to be called, so enqueue prefix is accurate in this context.- …

PassiveHookEffect…: This is real fun. What are passive hook effects?:

We have two categories of effects, passive (useEffect) and layout (useLayout). Imagine this component:

const App = () => {

useEffect(() => {

console.log('passive effect')

}, [])

useLayout(() => {

console.log('layout effect')

}, [])

}

Which of the effects will be called first? layout effect. Why? As mentioned in docs, layout effect is being called just after DOM mutation, but before browser render. Passive effects, on the other hand, are deferred (using scheduler module) to be called after browser render.

- …Mount: The easiest way to understand mount, as well as unmount hook effect is the example:

useEffect(() => {

// this is "mount" passive hook

return () => {

// this is "unmount" passive hook

}

}, [])

Depending on the state of the component, React Reconciler module calls mount or unmount (i.e. while destroying component).

To sum it up all passive effect hooks are being called asynchronously — after browser repaint. This is a different approach comparing to the old implementation of componentDidMount or componentDidUpdate which block the browser from repainting. It is also worth noticing, that we have no alternative for componentWillMount or componentWillUpdate in hooks world. Those methods used to be a great place to introduce side-effects by developers (which might delay repaint process) so that they decide to deprecate it.

So, all the code you put inside passive effect goes through the React Scheduler.

What is ‘isInputPending’?

This feature is a result of Facebook engineers’ struggles to shorten a time a user input (i.e. click, mouse, keyboard events) are being performed.

Let’s look at the example:

while (workQueue.length > 0) {

if (navigator.scheduling.isInputPending()) {

// Stop doing work if we have to handle an input event.

break;

}

let job = workQueue.shift();

job.execute();

}

Via navigator.scheduling.isInputPending() we can find out whether there is a pending user event (click, mouse, keyboard, drag&drop, etc.) so we can quickly react by yielding execution to the main thread (i.e. via the break statement) to handle the event.

Of course, it’s an experiment, not the official standard. It was available at the Chrome browser from version 74 to 78 (until Dec 4, 2019) as a part of Chrome Origin Trials.

You can read more about it both on Gihub as well as on Facebook’s engineering blog.

But why do I describe this thing here, in scheduler-based article? Well, the interesting fact is, that the current implementation of React Scheduler takes advantage of the feature:

After meeting specific requirements:

- our React app build has a feature flag enabled (

enableIsInputPending) - we use Google Chrome with experimental

navigator.scheduling.isInputPendingfeature enabled

our React Scheduler module provides an improved version of shouldYield implementation, which yields execution to the main thread when there is any pending event waiting to be executed.

History of scheduling in React

The problem with React 15.x was that the entire rendering process was being made synchronously. One, large, time-consuming, synchronous, and recursive (!) piece of code. This can’t co-operate with other browser activities, right?

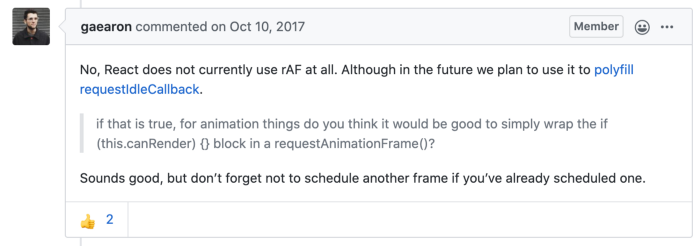

At the very beginning of React Fiber’s development (v. 16.x), the React team was using requestIdleCallback. But, it appeared to be — as Dan Abramov said — not as aggressive as the team wanted to.

The next step was to simulate requestIdleCallback with requestAnimationFrame. They tried to guess frame size and align React render mechanism with vsync cycle. And it was ok, until the latest made (by Andrew Clark) which gets rid of requestAnimationFrame, as described here).

Summary

As presented earlier, we have a couple of API which might be helpful while trying to implement scheduling mechanism, like requestAnimationFrame, requestIdleCallback, message loop (MessageChannel), or even setTimeout.

But hey — there were designed for slightly different purposes, weren’t they?

No doubt, the scheduling problem is on the table, some of the concepts have been announced lately within the browser vendor environments. If you are interested in the topic — I recommend WICG/main-thread-scheduling repo as well as its “Further Reading” section.